In light of the onset of the coronavirus disease (COVID-19), a lot of information is circulating around the novel illness. In particular, there is confusion on whether patent ownership of a disease-causing agent is allowed. As explained in the following article, patents associated with a virus are often regarding a treatment, not the virus itself. While it is possible to patent an actual virus, as the United States did with a strain of Ebola, the ability to do so has caused controversy in the past. So let’s take a look at the current IP surrounding COVID-19.

Agreements Behind the Potential Vaccines

One source of IP related to COVID-19 is the Collaborative Agreement between Generex Biotechnology Corporation (U.S.), Sinotek-Advocates International Industry Development (Shenzhen) Co., Ltd., and Beijing Zhonghua Investment Fund Management Co., Ltd. The collaboration is based on the technology behind a vaccine developed by Generex which has demonstrated enough effectiveness to qualify for the COVID-19 drug applications in China. According to the agreement, this technology addresses “potentially pandemic viruses” due to its cost-effective synthetic solution that combats the body’s vulnerability to novel viruses. The technology uses spike protein of the COVID-19 to stimulate T-helper cells. T-helper cells support both the antibiotic development and the cellular response against influenza (which has symptoms similar to those of coronavirus). T-helper cells also play a critical role in imparting an immunological ‘memory’ to new virus strains, as found with seasonal strains.

On March 3, 2020, just a few days after the collaboration agreement, Generex made effective a service agreement with EpiVax Inc. In this agreement, Generex is requesting the discovery and validation of the same technology licensed to Sinotek-Advocates and Beijing Zhonghua. The work plan involves EpiVax using their IP to develop from Generex’s technology another potential vaccine more customized for treating COVID-19.

Patents Behind the Potential Vaccines

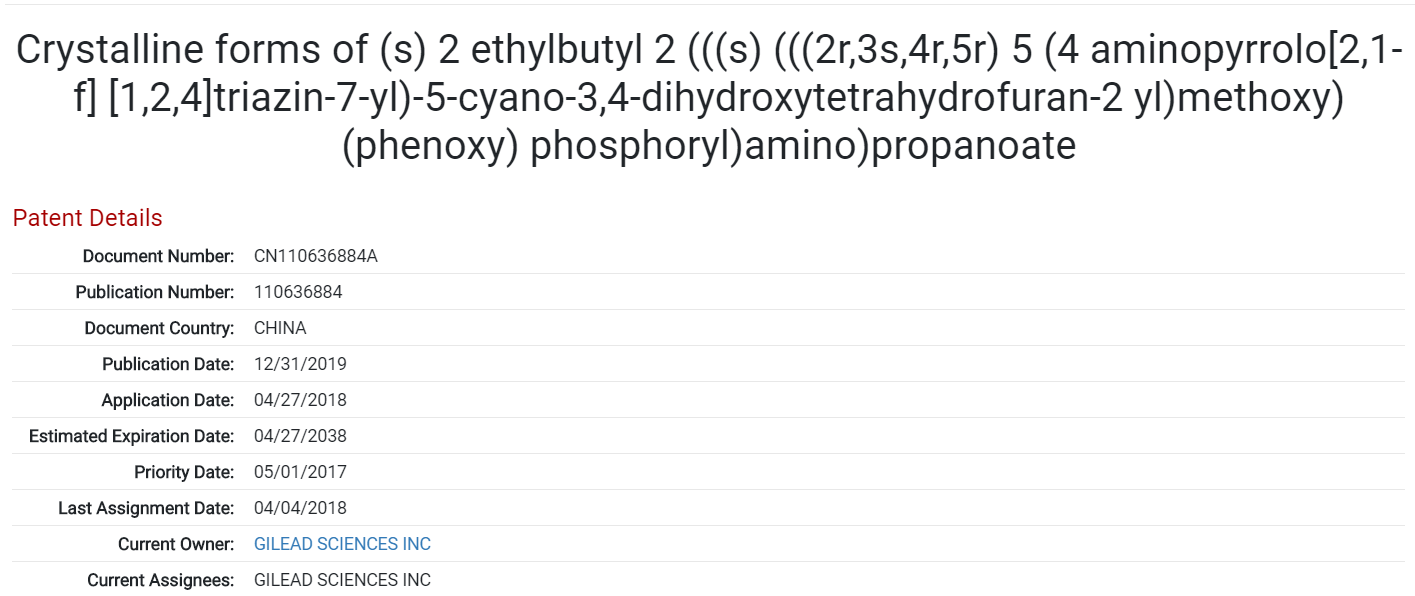

There are thousands of patents containing the term “coronavirus,” and all of them have application dates that precede the first known COVID-19 case (which is currently estimated to be around late November of 2019), so these patents naturally will not have the benefit of the information learned since the emergence of the novel virus. Currently, among patents containing the term “coronavirus,” patent application KR20190134578A applied for by a South Korean research university on November 27th, 2019 has the latest application date. However, this patent application concerns MERS-CoV, a strain of coronavirus that differs from the one causing COVID-19 (named SARS-CoV-2). A relevant filing by Gilead Sciences Inc. involves “Remdesivir,” a compound that has shown potential as a form of treatment for COVID-19. Though it has been stated that the technology behind Remdesivir was driven by the Ebola virus, the filings mention multiple virus families that can be targeted, with Coronaviridae being one of them. The Chinese patent application for Remdesivir (CN110636884A) is shown below.

One patent from the family of applications for Remdesivir, recently published in China and titled by its Medical Subject Heading (MeSH) chemical name. Source: Found in the ktMINE Patent Application

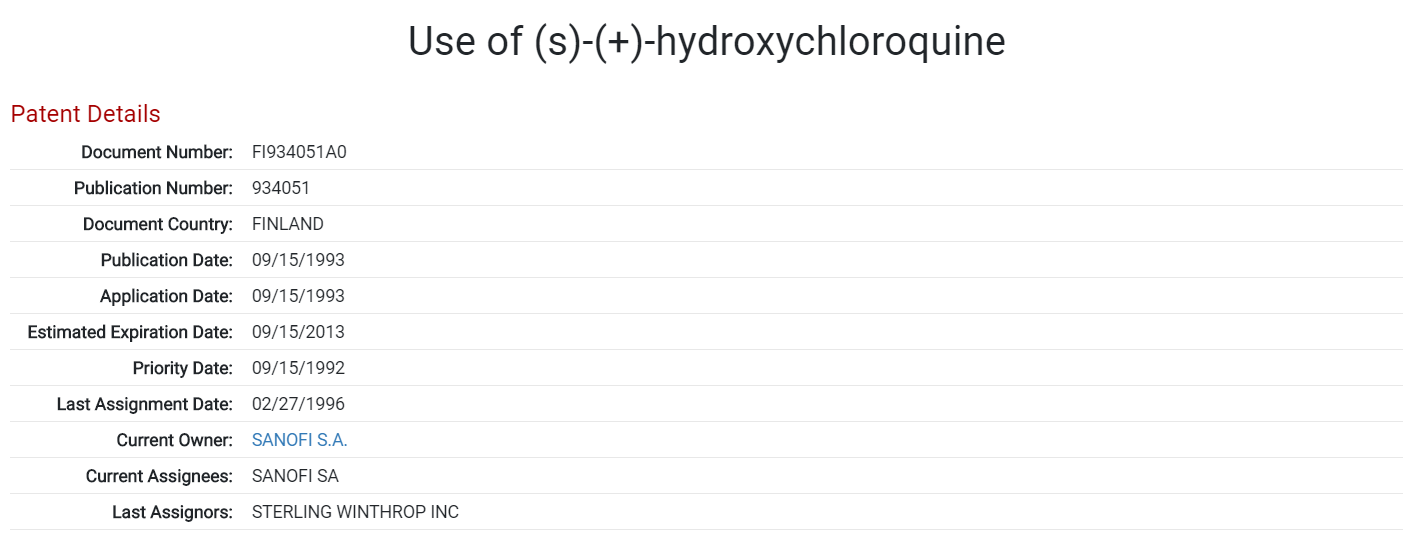

Two other drugs, chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine are also currently being investigated as treatments for COVID-19, both being treatments for malaria. Displayed below is a patent application for the use of hydroxychloroquine as a treatment for malaria, lupus erythematosus or rheumatoid arthritis. This is the oldest patent applied for by Sanofi S.A. relating to the drug. Sanofi was the initial marketer of the brand name versions of both hydroxychloroquine and chloroquine in the United States.

Patent for the use of hydroxychloroquine as a treatment for malaria, lupus erythematosus or rheumatoid arthritis. Applied for by Sanofi S.A. Source: Found in the ktMINE Patent Application

The Future of COVID-19 Treatment

There is a lot of ongoing research regarding a COVID-19 vaccine, and it takes time to develop a universally safe and effective drug. If the empirical outcome is similar to that of the MERS and SARS coronavirus strains, the best short-term solution may be therapeutic. Yet, there is always hope. In the case of influenza, there were multiple pandemics of various strains before a vaccine was implemented. The earliest recorded pandemic that fit the criteria of influenza occurred in 1580; starting in Asia and Russia, it spread to Europe, North-West Africa, and the Americas. Another notable pandemic referred to as the “Spanish” influenza arose in 1918 and resulted in a shocking record of 21 million deaths worldwide. It wasn’t until 1945 that inactivated influenza vaccines became available in the United States. In the 1960s, vaccines became recommended (by the US Commission on Influenza) for those at high risk of influenza complications.

In the end, it’s important to keep a balanced mindset and not overlook the importance of our part in this. In supplication to vaccinations, we can continuously strive to take precautions to prevent and manage contractions and transmission, pandemic or not, as best we can.